The early spring of 2004 found me on a southern island, in a garden, looking at a statue for which I had no explanation. “It’s Virginia Dare,” a friend said, but the Virginia Dare of my understanding was a child, the first European child born on these shores, part of the Lost Colony of Roanoke Island. This was a mature woman, nude except for a casual swag at her waist. And she was not blushing. I was enthralled.

I never know where my next obsession is coming from. This one came from an artist’s studio in Rome and made its way to the Elizabethan Gardens in Manteo, North Carolina, through scandal, shipwreck, fire and banishment. Up to the moment we met, I had simply thought I was on vacation, visiting friends, walking on the beach, gaping at osprey gliding above tall trees, and marveling that the trees had leaves in April, so unlike our own. But now I was on a quest which grew more fascinating at every turn, drawing in Nathaniel Hawthorne and a sculptor named William Wetmore Story, and a woman who had the mixed fortune to know them both, Louisa Lander.

Maria Louisa Lander was born in Salem, Massachusetts, in 1826 and was a precociously artistic child. She modeled heads for her dolls in clay and wax, carved figures in stone with a penknife, and, given better tools, carved a head in cameo from a shell “without the least instruction.” She grew up in her grandmother’s mansion surrounded by art. Her talents blossomed, and her family sent her to Europe to study. Rome, with its culture, stone cutters and ready supply of marble, was a natural destination.

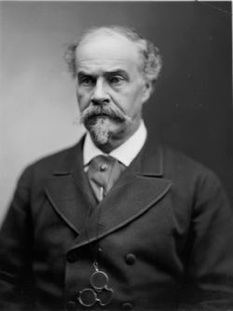

Louisa Lander sailed to Europe in 1855, and became the only pupil of sculptor Thomas Crawford, a New Yorker who had been working in Rome for 20 years. One biographer noted that Crawford had “the ardor of Irish temperament and the vigor of an American character,” while another said that he attracted “the very choicest spirits of the world of art and literature.” He was one of the few Americans to consider himself a permanent resident of Rome and was fluent in Italian as well as Romanesco. Crawford worked in a studio among the ruins of the Baths of Diocletian. The studio was described as “sprawling,” with 12 rooms and 50 assistants working on the sculptor’s many commissions.

Crawford’s work included the equestrian statue of George Washington at Richmond, Virginia, the statue of Beethoven in the Boston music hall, and in Washington, D.C., the U.S. Senate’s massive Progress of Civilization filling the pediment over the east entrance, and the giant Statue of Freedom, also known as Armed Liberty, that stands atop the Capitol Building.

Crawford had never accepted a student before, but took Lander as his first and only. He was the perfect mentor for the young woman from Salem, but tragically, just two years after her arrival, a tumor behind his left eye killed Thomas Crawford at the age of 44. Her mentor gone, Lander opened her own studio. And she traveled.

In London, Lander visited the British Museum, where she first learned the story of Virginia Dare and saw the watercolor drawings of John White, the leader and official artist of the expedition, who had returned to England with his pictures of the land, the flora and fauna, and the natives, including the woman shown at the left.

Virginia Dare was the first child to be born in North America of English parents. Elinor (White) Dare and Ananias Dare, were among the 117 settlers who left England on May 8, 1587, on an expedition sponsored by Sir Walter Raleigh. It was intended that the settlement would be established in the Chesapeake Bay area, but the captain of the ship, the Lion, landed his passengers instead on Roanoke Island, the site of an earlier, unsuccessful attempt at a colony.

Nine days after Virginia Dare’s birth, on August 27, 1587, John White left the colony for England, hoping to obtain aid and assistance. He arrived in England in November of 1587 as England was about to go to war with Spain. It was not until August of 1590 that White was able to return to Roanoke with a relief expedition. It found no trace of the settlers–only the word “Croatoan” carved on a post, the name of a nearby island and the tribe that lived there. The infant Virginia Dare, White’s granddaughter, had vanished along with the other Roanoke colonists, who were perhaps absorbed into the Croatan tribe.

Inspired by the story of Virginia Dare, Louisa Lander began a sculpture that would shock viewers for the next 100 years, imagining not a rosy cheeked English baby, but a young woman, now grown, English by birth, but living and dressed, barely, as a native.

* * *

Louisa Lander called on the Hawthorne family just five days after their arrival, and later, after seeing her work, Hawthorne agreed to sit for, and pay for, a bust of himself. No one anticipated what would come next: Over the course of 14 sittings, and 17 visits afterwards, Hawthorne was smitten. In his diary, he wrote of Lander:

“(She) is from my own native town, and appears to have genuine talent, and spirit and independence enough to give it fair play. She is living here quite alone, in delightful freedom, and has sculptured two or three things that may make her favorably known. ‘Virginia Dare’ is certainly very beautiful. During the sitting I talked a good deal with Miss Lander, being a little inclined to take a similar freedom with her moral likeness to that which she was taking with my physical one.

“There are very available points about her and her position: a young woman, living in almost perfect independence, thousands of miles from her New England home, going fearlessly about these mysterious streets, by night as well as by day; with no household ties, nor rule or law but that within her; yet acting with quietness and simplicity, and keeping, after all, within a homely line of right. In her studio she wears a sort of pea-jacket, buttoned across her breast, and a little foraging-cap, just covering the top of her head. She has become strongly attached to Rome, and says that when she dreams of home, it is merely of paying a short visit, and coming back before her trunk is unpacked.”

In The Marble Faun, Hawthorne more freely described Lander, barely veiled in the character of a painter, Miriam:

“… a beautiful woman, such as one sees only two or three, if even so many times, in all a lifetime; so beautiful, that she seemed to get into your consciousness and memory, and could never afterwards be shut out, but haunted your dreams, for pleasure or for pain; holding your inner realm as a conquered territory, though without deigning to make herself at home there.”

And then there is the bust itself, which speaks volumes: a young, strong, handsome Hawthorne, with naked shoulders, and full, sensual lips. The way Lander saw Hawthorne. The way Hawthorne felt in her presence.

And William Wetmore Story was now seeing his plum, his author, his American literary luminary, drawn from his control and into the orbit of a woman who openly defied him. Not only might he lose Hawthorne, but also his position of power.

What was to be done? To suggest to Hawthorne that his behavior had been improper was to suggest he was an adulterer and a liar, to insult him, and, for Story, to lose him.

But Louisa Lander was far more vulnerable. Over the summer, she traveled to America to secure more commissions. The Hawthorne family spent the summer in Florence. In the autumn, Lander returned to Rome carrying letters from home for the Hawthornes. But Story had been busy in her absence.

A rumor had been cultured that Lander had been on uncommonly familiar terms with a man, and that she had posed in the nude for other artists. Let us pause for a moment to savor the irony of these anonymous accusations. William Wetmore Story, and his contemporaries, regularly employed Italian women of the lower classes to model in the nude. They gazed upon naked women every day. With their hands, they fashioned their models’ breasts in clay. In Story’s case, that would include one breast for his Cleopatra, two petite breasts for his Dalilah, two lush breasts for his Libyan Sibyl, and two more for his Venus Anadyomene, who was portrayed totally nude.

And yet the rumor that Louisa Lander had perhaps posed in something less than full Victorian costume was to be the death knell of her reputation and her career as an artist. In her absence, Story summoned a tribunal of his own devising to afford Lander the opportunity to answer the charges. Of course, he knew she was not in Rome, nor would she have appeared if she had been, since she knew the charges to be baseless and the tribunal to be a farce.

And who would give them the Hawthorne family the news? What a surprise: It was the American painter Cephas Thompson, whose portrait of Hawthorne suddenly vaulted back into its position as the signature image of the famous author.

When Lander returned to Rome with letters for Nathaniel Hawthorne, he refused to see her. He never saw her again. William Wetmore Story had him in a neat little box. If Hawthorne defended Lander’s reputation, he would be admitting his own affection for her, for why else would he defend her against “all of Rome”?

And William Wetmore Story knew Nathaniel Hawthorne’s hot buttons. Of the nude statues Hawthorne viewed daily in Rome, he wrote, “I do not altogether see the necessity of ever sculpturing another nakedness. Man is no longer a naked animal; his clothes are as natural to him as his skin, and sculptors have no more right to undress him than to flay him.”

William Wetmore Story, the white-smocked, black-suited little prat, carried the day. Devoid of morality, he was instead plump with pride, misogyny and hypocrisy. He couldn’t get rid of Harriet Hosmer, the “manish” sculptor, because she had independent means. He couldn’t get rid of Charlotte Cushman, who had her own circle in London, nor of Edmonia Lewis, because she was sponsored in her work by influential abolitionists. And all were excellent sculptors, Lewis especially, an artist whose statue of Cleopatra was as striking and original as Story’s was cold and pedantic. (Today, her Cleopatra resides in the Smithsonian’s National Gallery, while Story’s sits in a dealer’s gallery in New York, looking for a buyer.) But Story, ever threatened and threatening, could get rid of Louisa Lander.

You might think that being shut off from such people would be a blessing to Lander, but more was involved. She made her living with her artistic talent, and suddenly there were no more commissions, no more patronage, no more wealthy visitors from America stopping by her studio. William Wetmore Story had succeeded in cutting her off not just from his artificial community, but ultimately from art itself.

At first, Louisa Lander defiantly continued to work but had to do so at her own expense because she had no commissions. Her example was being felt even in the United States. In 1859, Caroline Dall said, in addressing a Suffrage convention: “I honor women who act. That is the reason that I greet so gladly girls like Harriet Hosmer, Louisa Landor, and Margaret Foley. Whatever they do, or do not do, for Art, they do a great deal for the cause of labor.”

Running out of money, Louisa Lander returned to her home in Salem. But the rumors followed her there. She mounted an exhibition of her work in Boston in 1860, but soon after, the Civil War erupted and the nation was distracted from the world of art. Louisa Lander had been slandered and shunned. No new commissions came her way, and she stopped working, becoming more and more lonely, more and more embittered.

And what of the bust of Nathaniel Hawthorne? His son, Julian, told this story:

“The bust, which was a tolerable likeness in the clay, was put into marble in due course. But while it was undergoing this process, a mishap befell it. A gentleman — I will not mention his name, but he was an American and a person of culture — happened to be in Rome at the time the marble work was proceeding (of course under the hands of the regular workmen employed by sculptors for that purpose, and whose only business it is to reproduce accurately the model placed before them). Hawthorne and Miss Lander were both absent from Rome; and this critic, visiting the studio, noticed what he thought were some errors in the modeling of the lower part of the face, and directed the marble-cutters to make certain alterations, for which he accepted the responsibility. The result was, as might have been expected, that the likeness was destroyed; and the bust, in its present state, looks like a combination of Daniel Webster and George Washington, — as any one may see who pays a visit to the Concord Library, of which institution it is an appurtenance.”

This is accepted today as a lie. The family, embarrassed by the blatant sensuality of the bust, the rich, full lips, the naked shoulders, began telling stories on it almost immediately, disparaging the work, trivializing the work, doing all in their power to distance themselves, and hopefully others, from the obvious truth of the work.

Nor would William Wetmore Story ever again exert such power. Women artists continued to come to Rome, and the judgment of history on his reputation was not kind. In Modern Sculpture in America, published in 1896, the author noted that Story, “produced a series of cold, correct, pedantic statues, such as the Cleopatra, Semiramis, Medea, and Polyxena of the Metropolitan Museum, New York. In these works the classical spirit is already waning, and the American not at all apparent.” Russell Lynes in The Reader’s Companion to American History notes that Story was “as much a poet as a sculptor and short of genius at either.” Frederick Wegener refered to Story as “the undistinguished American sculptor who became the Brownings’ closest friend in Italy.”

What remained for William Wetmore Story was the decline of his influence, and one final piece of sculpture for which he would be remembered, a classic piece of kitsch, The Grieving Angel. Done for his wife’s grave in Rome, it depicts an angel, head bowed, draped over Emelyn Story’s gravestone in mourning. It is available today as both a garden sculpture and a desktop paperweight from Design Toscano.

Why the angel is grieving, however, has never been adequately explained. Would not the angels have rejoiced as they welcomed home Mrs. William Wetmore Story? Perhaps it was simply that William Wetmore Story thought so much of himself for so long, as the very hand of the Almighty on earth, that he could only imagine that the angels, his peers, would grieve as he did.

* * *

Louisa Lander’s statue of Virginia Dare walked a path much like that of its creator. Lander first tried to have the statue shipped from Rome to Boston, but the ship sank off the coast of Spain. After a year or two under water, the statue was raised by a Spanish salvage crew, at Lander’s expense. After its second voyage, the statue was spoken for by a collector who had it removed to his New York studio, which burned to the ground. The statue barely escaped; the collector did not. After his estate refused to pay Lander for the statue, she retrieved it and displayed it in Salem for the benefit of wounded soldiers. In 1863, she mounted an exhibition of her work in Boston where the Virginia Dare statue was labeled “the National Statue.” But she could not find another buyer.

Lander moved to Washington, D.C., and there the statue lived with her, catching the morning light in the bay window of her sitting room. Margaret Hudson, in her marvelous Searching for Virginia Dare: A Fool’s Errand, writes that Lander greeted Virginia Dare at the beginning of each new day, saying “You look beautiful this morning, Virginia.”

In 1893, Lander tried again to place the statue, offering to sell it to the North Carolina Commission for the Chicago World’s Fair, for display in the state’s exhibit. The state didn’t have the money, but the statue did find a champion, one Sallie Southall Cotten, a poetess and author of The Legend of Virginia Dare, who donned her Virginia Dare costume and presented her entire narrative poem in Lander’s sitting room. Won over, Lander agreed to will the statue to North Carolina.

In 1926, a few years after Lander’s death, the statue made its way to the Hall of History in Raleigh. There, in the company of some Confederate war heroes, it suffered at the hands of vandals and the wagging tongues of prudes, who hounded Virginia Dare into basement storage at the old Supreme Court Building. But it was soon to take a step closer to home.

In 1937, a playwright, teacher and author named Paul Green created a new dramatic form, the symphonic drama, a type of historical play, to be set on the site depicted in the action, with music, dance and poetic dialogue. The first of these was called The Lost Colony, the story of Sir Walter Raleigh’s doomed colony on Roanoke Island. Someone shipped the statue to the waterside theatre where the pageant was presented. But the North Carolina Parks Commission said there was no proof Virginia Dare had lived to adulthood, and thus the display of the statue would be inappropriate. They sent the much traveled and little loved statue on to Paul Green in Chapel Hill, who accepted it but left it in the case it arrived in.

Louisa Lander’s Virginia Dare awaited one more turn of the card. In 1950, the Garden Club of North Carolina proposed a traditional English flower garden to honor the Elizabethan heritage of Roanoke Island and serve as a memorial to Raleigh’s lost colony, which had settled, lived, and vanished on the site where the Gardens would stand. Donations poured in, including $100,000 worth of ancient Italian statuary from John Hay Whitney, and, in 1951, the white marble statue of Virginia Dare from Paul Green.

And so, after nearly 100 years after her creation, and 350 years after her subject’s birth, Virginia Dare came home to Roanoke Island.

* * *

In 1882, Phebe Hanaford wrote of Lander, “She executed ‘To-day’ and ‘Galatea,’ ‘Evangeline’ and ‘Elizabeth, the Exile of Siberia,’ all of them delightful each in its own way, and to these she has added ‘Undine,’ as a sculptured creation of beauty, ‘Ceres Mourning for Proserpine’ and ‘A Sylph.’… Miss Lander has continued to brighten the world of art by her genius. May she long live to mould clay, and chip marble into forms of loveliness!”

All of these works are lost. Louisa Lander died in Washington in 1923. One wonders if God arranges for meetings in heaven, if Louisa Lander and Paul Green have met, and, oh my goodness, here’s Virginia Dare.

* * *

The photograph of Louisa Lander’s statue at the Elizabethan Gardens in Manteo, Roanoke Island, N.C., is a pinhole photo taken by Gregg Kemp, May 2004. Thank you, Gregg.

The photograph of Louisa Lander’s bust of Nathaniel Hawthorne was provided by, and used here with the permission of, the Concord Free Public Library, Concord, Massachusetts.

Sources: The Marble Faun (1860) by Nathaniel Hawthorne; The French and Italian Note-Books of Nathaniel Hawthorne (1872); Daughters of America; or Women of the Century (1882) by Phebe A. Hanaford, pp. 285-6; Modern Sculpture In America (1896); William Wetmore Story and His Friends (1904) by Henry James; Bright Particular Star: The Life & Times of Charlotte Cushman (1970) by Joseph Leach; “Hawthorne Sits for Bust by Maria Louisa Lander” by John L. Idol, Jr., and Sterling Eisiminger, in Essex Institute Historical Collections (October 1978); Dearest Beloved: The Hawthornes and the Making of the Middle-Class Family (1993) by T. Walter Herbert; At Home in the Studio: The Professionalization of Women Artists in America (2001) by Laura R. Prieto; Searching for Virginia Dare: A Fool’s Errand (2002) by Marjorie Hudson; autograph of Louisa Lander from eBay. Thank you.

It makes me think about what Hawthorne wrote in The New Adam and Eve, just ten years before: “Chance, however, presents them with pictures of human beauty, fresh from the hand of Nature. As they enter a magnificent apartment, they are astonished, but not affrighted, to perceive two figures advancing to meet them. Is it not awful to imagine that any life, save their own, should remain in the wide world? [..] This miracle is wrought by a tall looking-glass, the mystery of which they soon fathom, because Nature creates a mirror for the human face in every pool of water, and for her own great features in waveless lakes. Pleased and satisfied with gazing at themselves, they now discover the marble statue of a child in a corner of the room, so exquisitely idealized, that it is almost worthy to be the prophetic likeness of their first-born. Sculpture, in its highest excellence, is more genuine than painting, and might seem to be evolved from a natural germ, by the same law as a leaf or flower.”

Quite the most wonderful feedback ever. Thank you.

Thank you so much for researching my grandfather’s great aunt. I am anxious to have a copy of this article. How might I go about it?

You’ve lost me. I am totally ignorant of posts, having stumbled upon yours by typing Louisa Maria Lander in the Google search bar. Is this article published in hard copy form? I am compiling an archive of writings about my ancestors and would very much like to know where I might get a copy of this one. Thank you.

Alice, I just stumbled upon your note while preparing to send this to a friend. If you send your address to me at akihmbo@gmail.com, I will print out and mail a copy of the piece to you. Kihm

Kihm.

You Sent the requested information to me over a year ago. Thanks again for your kind reply.

Alice

Sent from Yahoo Mail on Android

From:”Faithful Readers” Date:Mon, Apr 27, 2015 at 5:29 PM Subject:[New comment] Louisa Lander and Nathaniel Hawthorne

kihm commented: “Alice, I just stumbled upon your note while preparing to send this to a friend. If you send your address to me at akihmbo@gmail.com, I will print out and mail a copy of the piece to you. Kihm”

HI, thank you for this very interesting article on Hawthorne and Landor. I am doing research in preparation for a trip i am leading to Rome in May 2016, tracing Emerson, Hawthorne and others in the Eternal City. I want to go to the studio where Hawthorne sat for his portrait and for his sculpture.

You are so welcome! May your tour be a rousing success.

Hello Jenny,

Louisa Lander is my ancestor and I would be grateful for any tidbits of information you find on her while researching Nathaniel Hawthorne, especially the scandal resulting in her banishment from the artists’ colony. Thank you,

Alice.broadhurst@yahoo.com

I am just wondering, how do you know Lander saw the watercolours at the British Museum? It seems like a very interesting argument to make. Thank you Gloria gjbell@gmail.com

[…] came the next year. Lander’s story, slightly sensationalized, can be found in an engaging treatment by Kihm […]