Syracuse New Times, December 24, 1986

Like many traditions that set Christmas distinctly apart from other holidays – gift-giving, evergreens, holly, mistletoe and the wassail bowl – brewing a special holiday beer actually predates Christianity.

The tradition that recently brought F.X. Matt’s Season’s Best and other seasonal beers to market has roots in Greek mythology, Roman festivals and the religions of ancient Scandinavia, Germany and Britain. It has survived the merging of Christianity and the northern cultures, the Puritans in England and even American Prohibition.

Now many small brewers and brewpubs are once again brewing small batches of Christmas beers and ales, reviving the custom in America. With smaller brew kettles and fewer decision-makers, they find it easy to indulge their senses of whimsy and history. But even some larger brewers are catching the spirit. Adolph Coors of Golden, Colorado, has this year expanded a family and employee tradition to include its home state, offering one public run of its Winterfest beer.

San Francisco’s Anchor Brewing Company deserves much of the credit for the revival at the microbrewery level. Anchor’s Our Special Ale, now in its 12th year, is already legendary. Fritz Maytag, Anchor’s owner and the spiritual leader to the microbrewery movement, once said he wanted the beer to be “shocking” to the uninitiated, so idiosyncratic that it would never sell out. He got half his wish, but today the beer is snapped up and hoarded by fans, mailed coast to coast by true friends, and carried in baggage by lucky travelers.

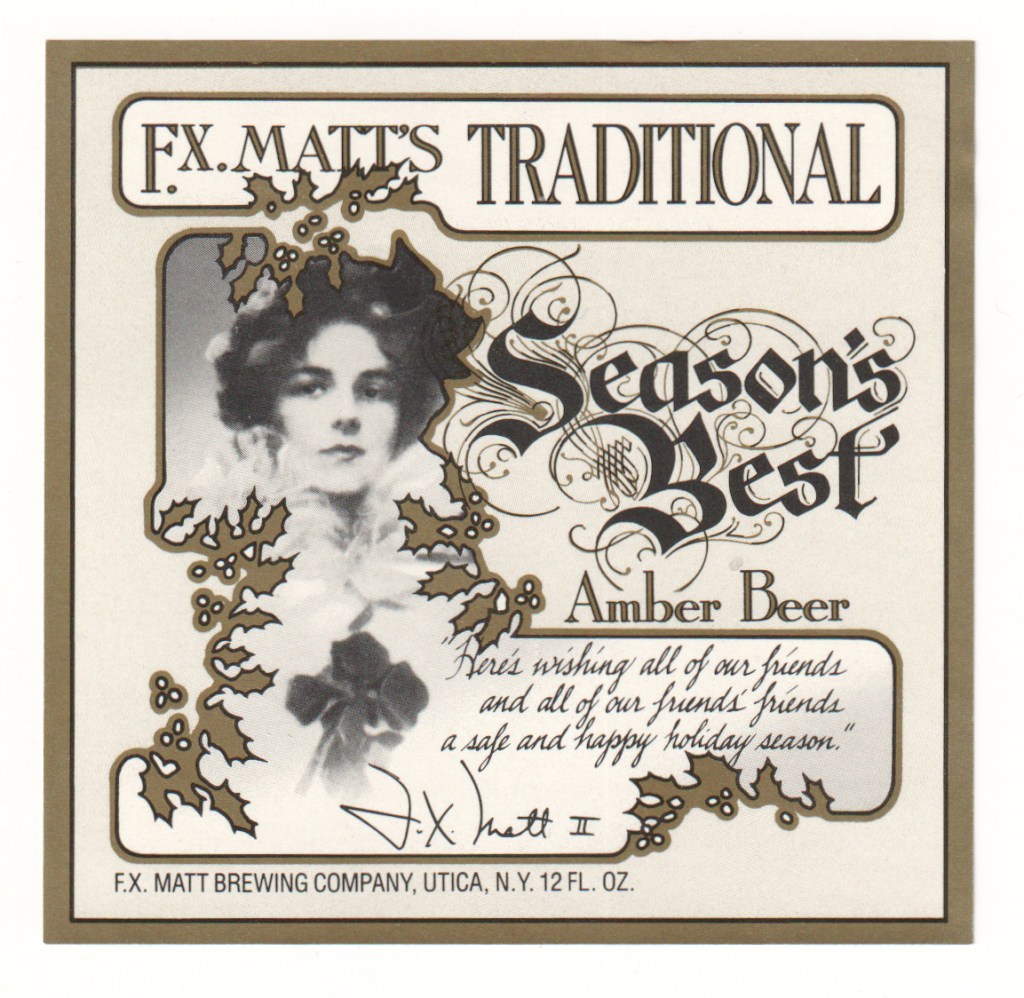

In Western New York, Fred Koch’s brewery in Dunkirk brewed a holiday beer for many years, until the brewery was absorbed by Genesee Brewing. But in 1983, the F.X. Matt Brewing Company of Utica brought back its holiday beer, Season’s Best.

The winter solstice – the darkest, shortest day of the year – provides the starting point for many holiday traditions, including these special brews. In Greek mythology, the weeks on either side of the winter solstice were a period of extended calm, called the Halcyon Days. In Rome, the same period encompassed Saturnalia, during which friends exchanged gifts, quarrels ceased and schools closed. The solstice itself was celebrated December 25th, as the Birthday of the Unconquered Sun, the return of light to the world.

In the 4th century after the birth of Christ, the Roman Church chose to set a date for the Nativity. Accounts differ but at some time between 336 and 354 they settled on December 25th to coincide with the winter solstice and turn the popular pagan holiday into a sacred holiday. Meanwhile, to the distant north and west of Rome, less-civilized Norsemen, Danes, Angles, Goths, Saxons and Jutes were celebrating Yule, also in honor of the winter solstice. This was an excellent time to brew and drink, because it fell in the off-season for making war.

While there is no record of their gift-giving or school closings, these simple folk brought the beer to the Christmas beer tradition. From before the time of Christ to their eventual conversion to Christianity, the northern barbarians were evolving from nomadic hunter-gatherers to farmers. As nomads, they drank beverages quickly fermented from wild barley, honey and apples. A regular supply of ale was established only when they settled and began growing grain.

As the Roman Empire spread northward, writers such as Pliny the Elder (23-79 AD) and Tacitus (c.55-c. 117 AD) noted the use of ale among the tribes Rome encountered. But Rome, despite occupying Britain for 350 years and their own conversion to Christianity, did not bring ale and the newly celebrated Christmas together. Gregory the Great, Pope from 590 to 604, gets the credit. Gregory sent a monk [who became known as Augustine of Canterbury] to England in 597 to convert Angles into “Angels.”

Like the princes of the Roman church before him, Gregory saw it was better to incorporate a tradition than to suppress it. Among the worshippers of Woden, the sacrifice of cattle or horses was common, accompanied by sacred feasting and drinking. In accordance with Pope Gregory’s advice, the animals were spared, but the feasting and drinking were converted into Church feasts and “Church Ales.” In particular, “Yuletide” feasts, common to the earliest traditions of Danes and Angles, were re-hallowed as “Christ Mass.”

Over the next 500 years, Christianity spread through all of Europe and Scandinavia. Where the church did not embrace and co-opt the customs of the pagans, the pagans often embraced the customs of the church. One Norse king, a convert to Christianity, decreed that the festival of Yule should begin at the same time as the Christmas of the church, and that every man should brew one batch of ale and keep the Yule holy as long as the brew lasted.

An American writer in 1908 [Edward R. Emerson in Beverages, Past and Present] found the Christmas beer tradition intact in Scandinavia. “Home brewing of ol – a native ale – has always been a practice in Scandinavia, and every farmer raises his own hops for the purpose,” he wrote. “Usually ol is an indifferent beverage, but at times one will meet with some in his travels that is really excellent. This is more apt to occur around the holidays, for at that time jule ol, or Christmas ale, is made and this, it is deemed, should be stronger and better than the ordinary beverage.”

Pope Gregory encouraged the Christmas beer tradition in England in another way, by establishing monasteries. The monastic network flourished for ten centuries, with interruptions for Viking pillaging and the Black Plague. Water being unhealthy, beer was the basic drink of the monks and they did much to perfect its brewing.

Various German convents and monasteries – the first to use hops and to develop lager beer – also brewed special beers for special occasions. Perhaps they meditated often on the belief that Christ’s first miracle was fermentation (John 2:1-11). Special prayers were offered up for the cellarer and the success of his brew. On holidays, while “doing the great 0” [zero work, referenced in The Curiosities of Ale and Beer (1886) by John Bickerdyke], an extra portion of ale was dispensed to all.

Outside monasteries, most beer was made in the home, where it was a job for women. (This continued until beer was found to have monetary value.) So it was natural to make a special brew for the holidays, just as we would bake a cake for a birthday today. Without bottling or any other way to preserve beer, it was consumed as it was made, and the next batch begun almost immediately. Thus there was a weekly opportunity for special beers.

In the Saxon villages of England, as the worship of Woden and Thor gradually died out, life came to revolve around the parish church. Ale was used for baptisms and sometimes substituted for the communion wine. Members of the congregation sold ale to the church and got it back as a reward for their tithes. It was the official drink of celebrations in a whole series of church holidays.

Strong ale was reserved for holidays simply because people did not have to work, and thus could devote themselves to drinking and its consequences. Since ales brewed in colder weather were brewed to a higher alcohol content to serve as winter warmers, Christmas was the perfect occasion for a special ale.

In the Middle Ages, the holiday became a great popular festival that warranted its own brew, just as Yule had in the days before Christianity. But later, when reformers objected to revelry on such holy days, observance was forbidden in England under the Puritanical Commonwealth (1644-1660). Traditional roast boar, with an apple in its mouth to represent the sun at the darkest time of the year, was one of the casualties.

But Christmas ales survived. They really had everything going for them: the relief and gratitude engendered by the return of the light of the world, a holiday in which to be consumed, and two millennia of religious tradition.

When commercial brewing grew in the 15th and following centuries, the commercial brewers continued the traditions of church and home. Today, Scandinavians still brew Jule Ol, Germans make winter beer, and Christmas ales are brewed in England. As American brewing traditions came from these countries, so did Christmas beers. May many come your way this holiday season, and may you drink them safely and happily.

***

The Season’s Best label was beautifully designed by Tim Ransom.

[…] “The Beers of Christmas”Syracuse New Times, December 24, 1986Origins of the holiday beer tradition […]